- Home

- Dornford Yates

Brother of Daphne Page 13

Brother of Daphne Read online

Page 13

“Oh, Boy!” cried Jill excitedly.

“I want to see it awfully,” said Daphne.

“Why rush upon your fate?” said her husband.

“I hope you’ll like it,” said I nervously.

“Where are we going to bury – I mean, hang it?” said Jonah.

“What about the potting-shed?” said Berry. “We can easily move the more sensitive bulbs.”

“If it’s good,” said Daphne, “we’ll have it in the library.”

“I object,” said her husband. “I don’t want to be alone with it after dark.”

I smiled upon him. Then:

“Bur-rother,” said I. “I like to think that I shall be always with you. Though in reality harsh leagues may lie between us, yet from the east wall of the library, just above the typewriter, I shall smile down upon your mis-shapen head a peaceful, forgiving smile. What a thought! And you will look up from your London Mail and—”

“Don’t,” said Berry, emitting a hollow groan. “I am unworthy. Unworthy.” He covered his face with his hands. “Where is the Indian Club?” he added brokenly, “I don’t mean the one in Whitehall Court. The jagged one with nails in it. I would beat my breast. Unworthy.”

“Conundrum,” said Jonah. “Where were the worthy worthies worthy?”

“I know,” said I. “They were worthy where they were.”

“Where the blaze is,” said Berry.

“The right answer,” said Jonah, “is Eastbourne.”

Daphne turned to Jill. “Is the trick-cycle ready, dear? We’re on next, you know.”

Here a servant came in and announced that a picture had come for me.

We poured into the hall. Yes, it had come. In the charge of two messenger boys and a taxi, carefully shrouded in sackcloth.

Berry touched the latter and nodded approval. Then he turned to the boys.

“Are there no ashes?” he said.

We bore it into the dining-room and set it upon a chair by the side of a window. I took out my knife and proceeded to cut the string.

“Wait a moment,” said Jonah. “Where’s the police whistle?”

“It’s all right,” said Berry. “James has gone for the divisional surgeon.”

I pulled off the veil.

It was really a speaking likeness of Margery.

Two hours later the telephone went.

I picked up the receiver.

“Is that six – o – four – o – six Mayfair?” – excitedly.

Margery’s voice.

“It is,” said I.

“Oh, is that you?”

“It is.”

“Oh, d’you know, the most awful thing has happened.”

“I know,” I said heavily.

“Then you have got mine?”

“Yes.”

“I suppose you guessed I’ve got yours?”

“You don’t sound very sympathetic,” – aggrievedly.

“My dear, I’m—”

“You don’t know what I’ve been through.” This tearfully.

“Don’t I?” I said wearily.

8: The Busy Beers

“They never sting some people,” said Daphne.

“Perhaps,” said I, “perhaps that is because they never get the chance. It doesn’t offer, as they say.”

“Oh, yes, they do. They simply don’t sting them.”

“’M. During Lent, I suppose?” I murmured drowsily. A May afternoon can be pleasantly hot.

“It’s a sort of power they have,” said Daphne mercilessly.

I opened my eyes.

“The bees? It’s a very offensive power.”

“No, Boy, the people. They simply swarm all over some persons, and it’s all right.”

I shuddered.

“Perhaps,” said Berry, looking at me, “perhaps you have that power. Who knows?”

“Who will ever know?” said I defiantly.

“We can easily find out,” said Berry eagerly.

I sat up. “It is,” I said, “just conceivable that I have that power. I do not recollect my immersion in the Styx, but it is, I suppose, not impossible that, although I am not actually invulnerable, my sterling qualities may yet be so apparent to the bee mind that, even were I so indiscreet as to lay hands upon their hive, they would not so far forget themselves as to assail me. At the same time, it is equally on the cards that the inmates of the hive I so foolishly approached would be a dull lot – shall we say, Bœotian bees? Or an impulsive lot, who sting first and look for qualities afterwards. In short, mistakes will occur, and, as an orphan and a useful member of society, I must refuse to gratify your curiosity.”

“I think you might try,” said Daphne. “We want them to swarm awfully, and they might actually swarm on you. You never know.”

“Pardon me, I do know. I have no doubt that they would swarm on me. No doubt at all.”

“Well, then—”

“Disobliging of me not to let them, isn’t it? And we could have the funeral one day next week. What are you doing on Tuesday?”

“Well, we’ve got to move them from the skep into the new hive tonight somehow,” said my sister, “and you’ve got to help.”

“Oh, I’Il help right enough.”

“What’ll you do?”

“I’Il go up the road and send the traffic round by West Hanger. We don’t want to be hauled up for manslaughter.”

Daphne turned to Berry.

“He’d better hold the skep, I think,” she said simply.

“Yes,” said her husband. “Or keep the new hive steady while we shake the bees out of the skep into it. We’ve only got two veils, but he won’t want one for that.”

“Of course not,” said I with a bitter laugh. “In fact, I think I’d better wear a zephyr and running shorts. I shall be able to move with more freedom.”

“Ah, no,” said Berry. “You must keep the trunk covered. The face and hands don’t really matter, but the back and legs… That might be dangerous.”

“Nonsense, nonsense,” said I. “I’m not afraid of a bee or two. How many are there in the hive?”

“Twenty or twenty-five thousand,” said Daphne. “Where are you going?”

“To set my house in order. Heaven forgive you, as I do. I have already forgiven Berry. I should like Jonah to have my stop-watch.”

As I walked across the lawn, I heard the wretched girl reading from The Busy Bee Keeper:

“Toads are among the bees’ most deadly enemies. They will sit at the mouth of a hive and snap up bees as fast as they emerge…”

Till then I had always been rather against toads.

I well remember the day on which I learned of the purchase of the bees. It had been raining the night before and all day the clouds hung low and threatening. Misfortune was in the air. Their actual advent I do not recollect, for when I had heard that they were to arrive on Saturday night, I had made a point of going away for the weekend.

On my return I avoided the kitchen garden assiduously for several days, but after a while I began to get used to the presence of the bees, and their old straw home – I could see it from my bedroom – looked rather pretty and comfortable.

Then Daphne, who never will leave ill alone, had announced that they must be moved into a new hive.

In vain I characterized her project as impious, wanton, and indecent in turn.

A new hive, something resembling a Swiss chalet, was ordered, and with it came two pairs of gauntlets and some veils which looked like meat-safes. Oh yes, and a ‘smoker’.

The ‘smoker’ was the real nut.

At a distance of five paces this useful invention might have been mistaken for a small cannon. As a matter of fact, it consisted of a pair of bellows, with the nozzle, which was very large, on the top instead of at the end. As touching the ‘smoker’ the method of procedure was as follows: – One lighted a roll of brown paper, blew it out again and placed it in the nozzle. Then, telling the gardener’s boy to stand by with the salvolatile,

one began to blow the bellows. Immediately the instrument belched forth clouds of singularly offensive smoke.

One might think that, if this were done in the vicinity of a hive, such a proceeding would tend to irritate the bees into a highly dangerous, if warrantable, frenzy, and that they would take immediate steps to abate the nuisance in their own simple way. But that, my brothers, is where we are wrong. Where bees are concerned, the ‘smoker’s’ fumes are of a soporific and soothing nature. Indeed, before a puff of its smoke a bee’s naughty malice and resentment disappear, and the bee itself sinks, gently humming, into the peaceful, contented slumber of a little che-ild.

At least, that was what the books said.

Seven o’clock that evening found us huddled apprehensively together outside the kitchen garden, talking nervously about the Budget. All was very quiet. A fragrant blue smoke stole up gently from the ‘smoker,’ which I held at arm’s length. Berry and Daphne were arrayed in veils and gauntlets. They reminded me irresistibly of Tenniel’s Tweedledum and Tweedledee.

“Mind you’re ready with the ‘smoker’ when I want it,” said Berry shortly.

“I – er – I thought you’d take it with you,” I said uneasily.

“Nonsense,” said Daphne. “We can’t do everything. You must be ready to hand it to Berry if the bees get infuriated.”

Thank you.

“Look here,” said I, “I’m sure I shall do something wrong. You’d much better have the gardener’s boy.”

“And have to pay him hundreds of pounds compensation. I don’t think,” said Berry.

At the mention of compensation I started violently and dropped the ‘smoker’. When I had picked it up:

“Look here,” I said, “I’ll stand on the path and keep the beastly thing smoking and if – if they should get – er – excited, well – er – there it’ll be all ready for you.”

“Where?” said Daphne suspiciously.

“On the path.”

“And you?”

“I shall probably be just getting my second wind.”

They looked at one another and sneered into their veils.

“It’s murder,” I said desperately, “sheer murder. You ask my death.”

The stable clock chimed a quarter past seven.

We entered the kitchen garden in single file.

The hive was as silent as the tomb. It seemed almost wicked to–

All went well until Berry was on the point of lifting the skep. Suddenly something jumped in the wallflowers by Daphne, and she started against her husband with a little scream. It was a toad. I felt braver. We were not alone. But my pleasure was short-lived. Berry’s hand had been upon the skep and the jolt had aroused the bees.

Up rose an angry murmur. I felt instinctively it was an angry one.

My brother-in-law had the ‘smoker’ in his hand. They told me afterwards that I had gone and given it him. That shows the state I was in. I was not responsible for my actions.

With all speed he applied the nozzle to the mouth of the skep. He was in time to stop the main body, but a few had already emerged.

I stood as if rooted to the spot.

Immediately seven bees alighted on Berry’s left hand. I saw them black against the white of his gauntlet. Spellbound I watched him train the ‘smoker’ upon them one by one. Three rolled slowly off before as many puffs, intoxicated, doubtless, with delight and drunk with ecstasy. The fourth one he missed. The fifth moved as he was shooting and he missed again. Then he got nervous and tried to please two at once. The sixth began to buzz and four more arrived.

Berry lost his head and began to shoot wildly. One settled on Daphne’s veil and she screamed. The hive began to hum again. With mistaken gallantry, Berry left the bees on his gauntlet and turned to the one on his wife’s veil. The next moment she was reeling against the wall in a paroxysm of choking coughs. Some more of the twenty-five thousand began to emerge from the skep, and a moment later I was stung in the lobe of the right ear.

The pain, I may say, was acute, but it certainly broke the spell, and I turned and ran as I have never run before.

Across the garden, down the drive, out of the lodge gates, over a hedge, with eighteen inches to spare, and across country like a thoroughbred.

At last I plunged into a roadside wood almost on the top of a girl. She stared at me.

“Lie down,” I gasped.

“Why?”

“Never mind why. Lie down for your life.”

She lay down wonderingly beside me, as I sobbed and panted in the undergrowth.

At last, after cautioning her to keep quiet, I listened long and carefully. The result was satisfactory. My escape was complete.

I turned my attention to the girl. She was sitting up now regarding me with big eyes.

Her hair was almost hidden under a big-brimmed garden hat, but I could see her face properly. Her features were delicate and regular, and her mouth was small and red. Steady grey eyes. She was wearing a soft blue dress of linen, and her brown arms were bare to the elbow. In her hand she had a posy of wild flowers. Little shoes of blue, untanned leather, I think it is. She was slender and lithe to look at, and the flush of health glowed in her cheeks.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “It all comes of beeing. If we hadn’t been beeing—”

“And yet he doesn’t look mad,” she said musingly.

“I’m not mad,” I said. “I admit that if I had on a bonnet, I should have several bees in it. Happily I lost it at the water jump. I’m a beer.”

“A what?” she said, recoiling.

“A beer. At least I was one. Two other beers were with me – busy beers. Stay,” I went on, “be of good beer – I mean cheer. I do not refer to the beverage of that name. By ‘beer’ I mean one actively interested in bees.”

She looked more reassured.

“Why were you running?”

I spread out my hands.

“The beggars were at my heels.”

“By which you mean—”

“That the inmates of the hive in which I was just now actively interesting myself, resented such active interest and endeavoured to fall upon me in great numbers.”

“And you escaped unhurt?”

“Except that at the outset I was winged in the ear, I have baulked them of their prey. Selah!”

“I had an idea that the person of a beer was sacred.”

“So it is, my dear. But these were impious bees, dead to all sense of right and wrong. They’ve done themselves in this time. Guilty of sacrilege and brawling, they may shortly expect a great plague of toads. It will undoubtedly come upon them. I shall curse them tomorrow morning directly after breakfast.”

“Have you really been stung?”

“Every time.”

“How exciting.”

“Perhaps. But it’s very overrated, believe me.”

“Let me look.”

I submitted readily.

After a brief scrutiny my lady announced that she could see the sting. Her fingers dealt very gently with the injured lobe, and by dint of looking out of the far corners of my eyes, I just managed to command a prospect of one grey eye and half the red mouth. Her lips were parted and she was smiling a little.

“If I didn’t love your mouth when you smile, I should be inclined to suggest that it was nothing to laugh about,” I said reprovingly.

The grey eye met mine. Then she laid a small cool hand firmly on my chin and pushed it round and away.

“Otherwise I can’t see properly,” she explained. Then, “I believe I can dig it out,” she said quietly.

I broke away at that and looked round. She was quite serious and began to unfasten a gold safety pin.

“Look here,” I said hurriedly. “You’re awfully kind; but, you know, as it is in, don’t you think perhaps it had better stay in? I mean, after all, a sting in the ear—”

She just waved my head round and began.

“Police,” I said feebly. “Assault and wounding stalk

in your midst. Police.”

She really got it out very well…

“And so you live here?” she said, after a while.

“In the vicinity,” said I. “About a mile and a half away as the crow flies or a beer runs – the terms are synonymous, you know. Large, grey, creepered residence, four reception, two bed, six bath, commands extensive views, ten minutes from workhouse, etc., etc.”

“Is it ‘White Ladies?’”

“It is. From which you now behold me an outcast – a wanderer upon the face of the earth. But how did you know?”

“They’ll be quiet by now,” she said, ignoring my question. “The bees, I mean.”

“I’m not so sure.”

She rose to her knees, but I laid a hand on her shoulder.

“What are you going to do, lass?”

“I shall be late for dinner.”

“Your blood be upon your head. The bees certainly will.”

“Nonsense.”

“I have no doubt they are at this moment going about like raging lions seeking upon whom they may swarm.”

“Must I pass your house?”

“To get to the village you must.”

“Well I’m going, anyway.”

I rose also. She stared at me and her glad smile settled it.

“One must die some time,” said I, “and why not on a Wednesday?”

It was with no little misgiving that I stepped out into the road, and walked beside her towards the village. As we approached White Ladies, a solitary bee sang by us and startled me. My nerves were on edge. I breathed more freely when we had passed the lodge gates. All was very still. The village lay half a mile further on.

Suddenly she caught at my arm. Behind us came from a distance a faint, drowsy hum. Even as we listened, it grew louder.

The next second we were running down the straight white road, hand in hand and hell for leather.

She ran nobly, did the little girl. But all the time the hum was getting more and more distinct.

I wondered if the village would ever come. It seemed as if someone had moved it since the morning.

About the first house was the old Lamb Inn, with its large stableyard. There stood a lonely brougham, horseless with upturned shafts. The yard was deserted.

Berry and Co.

Berry and Co. Jonah and Co.

Jonah and Co. The Funny Bone: Short Stories and Amusing Anecdotes for a Dull Hour

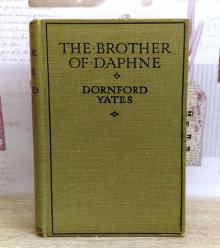

The Funny Bone: Short Stories and Amusing Anecdotes for a Dull Hour The Brother of Daphne

The Brother of Daphne Courts of Idleness

Courts of Idleness Ne'er Do Well

Ne'er Do Well She Painted Her Face

She Painted Her Face Safe Custody and Laughing Bacchante

Safe Custody and Laughing Bacchante As Berry and I Were Saying

As Berry and I Were Saying And Berry Came Too

And Berry Came Too Valerie French (1923)

Valerie French (1923) Brother of Daphne

Brother of Daphne Berry Scene

Berry Scene Gale Warning

Gale Warning B-Berry and I Look Back

B-Berry and I Look Back Storm Music (1934)

Storm Music (1934) House That Berry Built

House That Berry Built